eJournal: uffmm.org,

ISSN 2567-6458, 22.February 2019

Email: info@uffmm.org

Author: Gerd Doeben-Henisch

Email: gerd@doeben-henisch.de

Last change: 23.February 2019 (continued the text)

Last change: 24.February 2019 (extended the text)

CONTEXT

In the overview of the AAI paradigm version 2 you can find this section dealing with the philosophical perspective of the AAI paradigm. Enjoy reading (or not, then send a comment :-)).

THE DAILY LIFE PERSPECTIVE

The perspective of Philosophy is rooted in the everyday life perspective. With our body we occur in a space with other bodies and objects; different features, properties are associated with the objects, different kinds of relations an changes from one state to another.

From the empirical sciences we have learned to see more details of the everyday life with regard to detailed structures of matter and biological life, with regard to the long history of the actual world, with regard to many interesting dynamics within the objects, within biological systems, as part of earth, the solar system and much more.

A certain aspect of the empirical view of the world is the fact, that some biological systems called ‘homo sapiens’, which emerged only some 300.000 years ago in Africa, show a special property usually called ‘consciousness’ combined with the ability to ‘communicate by symbolic languages’.

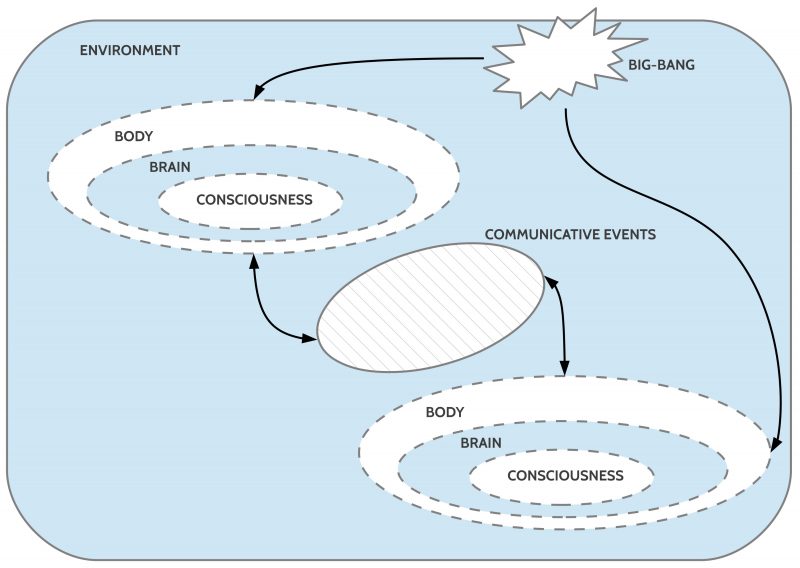

As we know today the consciousness is associated with the brain, which in turn is embedded in the body, which is further embedded in an environment.

Thus those ‘things’ about which we are ‘conscious’ are not ‘directly’ the objects and events of the surrounding real world but the ‘constructions of the brain’ based on actual external and internal sensor inputs as well as already collected ‘knowledge’. To qualify the ‘conscious things’ as ‘different’ from the assumed ‘real things’ ‘outside there’ it is common to speak of these brain-generated virtual things either as ‘qualia’ or — more often — as ‘phenomena’ which are different to the assumed possible real things somewhere ‘out there’.

PHILOSOPHY AS FIRST PERSON VIEW

‘Philosophy’ has many facets. One enters the scene if we are taking the insight into the general virtual character of our primary knowledge to be the primary and irreducible perspective of knowledge. Every other more special kind of knowledge is necessarily a subspace of this primary phenomenological knowledge.

There is already from the beginning a fundamental distinction possible in the realm of conscious phenomena (PH): there are phenomena which can be ‘generated’ by the consciousness ‘itself’ — mostly called ‘by will’ — and those which are occurring and disappearing without a direct influence of the consciousness, which are in a certain basic sense ‘given’ and ‘independent’, which are appearing and disappearing according to ‘their own’. It is common to call these independent phenomena ’empirical phenomena’ which represent a true subset of all phenomena: PH_emp ⊂ PH. Attention: These empirical phenomena’ are still ‘phenomena’, virtual entities generated by the brain inside the brain, not directly controllable ‘by will’.

There is a further basic distinction which differentiates the empirical phenomena into those PH_emp_bdy which are controlled by some processes in the body (being tired, being hungry, having pain, …) and those PH_emp_ext which are controlled by objects and events in the environment beyond the body (light, sounds, temperature, surfaces of objects, …). Both subsets of empirical phenomena are different: PH_emp_bdy ∩ PH_emp_ext = 0. Because phenomena usually are occurring associated with typical other phenomena there are ‘clusters’/ ‘pattern’ of phenomena which ‘represent’ possible events or states.

Modern empirical science has ‘refined’ the concept of an empirical phenomenon by introducing ‘standard objects’ which can be used to ‘compare’ some empirical phenomenon with such an empirical standard object. Thus even when the perception of two different observers possibly differs somehow with regard to a certain empirical phenomenon, the additional comparison with an ’empirical standard object’ which is the ‘same’ for both observers, enhances the quality, improves the precision of the perception of the empirical phenomena.

From these considerations we can derive the following informal definitions:

- Something is ‘empirical‘ if it is the ‘real counterpart’ of a phenomenon which can be observed by other persons in my environment too.

- Something is ‘standardized empirical‘ if it is empirical and can additionally be associated with a before introduced empirical standard object.

- Something is ‘weak empirical‘ if it is the ‘real counterpart’ of a phenomenon which can potentially be observed by other persons in my body as causally correlated with the phenomenon.

- Something is ‘cognitive‘ if it is the counterpart of a phenomenon which is not empirical in one of the meanings (1) – (3).

It is a common task within philosophy to analyze the space of the phenomena with regard to its structure as well as to its dynamics. Until today there exists not yet a complete accepted theory for this subject. This indicates that this seems to be some ‘hard’ task to do.

BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN BRAINS

As one can see in figure 1 a brain in a body is completely disconnected from the brain in another body. There is a real, deep ‘gap’ which has to be overcome if the two brains want to ‘coordinate’ their ‘planned actions’.

Luckily the emergence of homo sapiens with the new extended property of ‘consciousness’ was accompanied by another exciting property, the ability to ‘talk’. This ability enabled the creation of symbolic languages which can help two disconnected brains to have some exchange.

But ‘language’ does not consist of sounds or a ‘sequence of sounds’ only; the special power of a language is the further property that sequences of sounds can be associated with ‘something else’ which serves as the ‘meaning’ of these sounds. Thus we can use sounds to ‘talk about’ other things like objects, events, properties etc.

The single brain ‘knows’ about the relationship between some sounds and ‘something else’ because the brain is able to ‘generate relations’ between brain-structures for sounds and brain-structures for something else. These relations are some real connections in the brain. Therefore sounds can be related to ‘something else’ or certain objects, and events, objects etc. can become related to certain sounds. But these ‘meaning relations’ can only ‘bridge the gap’ to another brain if both brains are using the same ‘mapping’, the same ‘encoding’. This is only possible if the two brains with their bodies share a real world situation RW_S where the perceptions of the both brains are associated with the same parts of the real world between both bodies. If this is the case the perceptions P(RW_S) can become somehow ‘synchronized’ by the shared part of the real world which in turn is transformed in the brain structures P(RW_S) —> B_S which represent in the brain the stimulating aspects of the real world. These brain structures B_S can then be associated with some sound structures B_A written as a relation MEANING(B_S, B_A). Such a relation realizes an encoding which can be used for communication. Communication is using sound sequences exchanged between brains via the body and the air of an environment as ‘expressions’ which can be recognized as part of a learned encoding which enables the receiving brain to identify a possible meaning candidate.

DIFFERENT MODES TO EXPRESS MEANING

Following the evolution of communication one can distinguish four important modes of expressing meaning, which will be used in this AAI paradigm.

VISUAL ENCODING

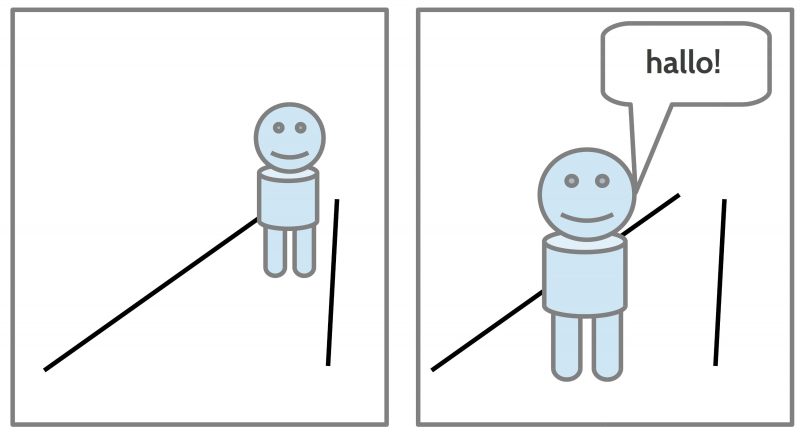

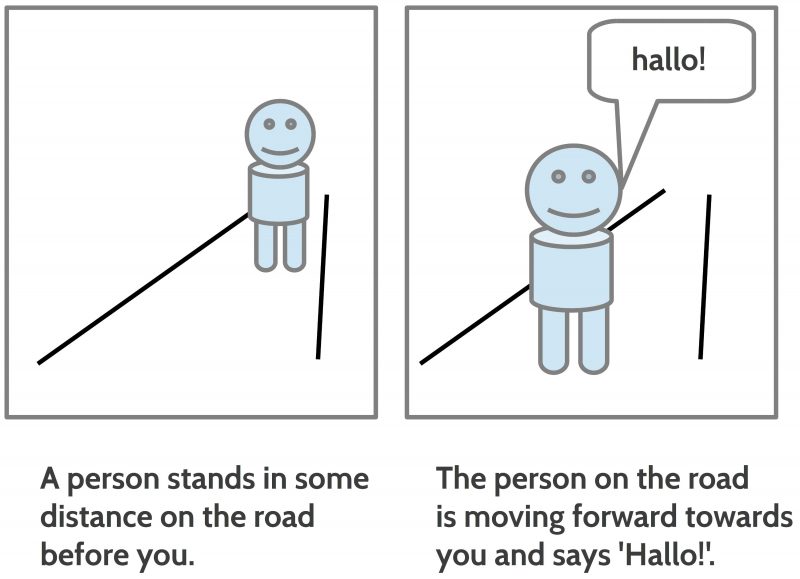

A direct way to express the internal meaning structures of a brain is to use a ‘visual code’ which represents by some kinds of drawing the visual shapes of objects in the space, some attributes of shapes, which are common for all people who can ‘see’. Thus a picture and then a sequence of pictures like a comic or a story board can communicate simple ideas of situations, participating objects, persons and animals, showing changes in the arrangement of the shapes in the space.

Even with a simple visual code one can generate many sequences of situations which all together can ‘tell a story’. The basic elements are a presupposed ‘space’ with possible ‘objects’ in this space with different positions, sizes, relations and properties. One can even enhance these visual shapes with written expressions of a spoken language. The sequence of the pictures represents additionally some ‘timely order’. ‘Changes’ can be encoded by ‘differences’ between consecutive pictures.

FROM SPOKEN TO WRITTEN LANGUAGE EXPRESSIONS

Later in the evolution of language, much later, the homo sapiens has learned to translate the spoken language L_s in a written format L_w using signs for parts of words or even whole words. The possible meaning of these written expressions were no longer directly ‘visible’. The meaning was now only available for those people who had learned how these written expressions are associated with intended meanings encoded in the head of all language participants. Thus only hearing or reading a language expression would tell the reader either ‘nothing’ or some ‘possible meanings’ or a ‘definite meaning’.

If one has only the written expressions then one has to ‘know’ with which ‘meaning in the brain’ the expressions have to be associated. And what is very special with the written expressions compared to the pictorial expressions is the fact that the elements of the pictorial expressions are always very ‘concrete’ visual objects while the written expressions are ‘general’ expressions allowing many different concrete interpretations. Thus the expression ‘person’ can be used to be associated with many thousands different concrete objects; the same holds for the expression ‘road’, ‘moving’, ‘before’ and so on. Thus the written expressions are like ‘manufacturing instructions’ to search for possible meanings and configure these meanings to a ‘reasonable’ complex matter. And because written expressions are in general rather ‘abstract’/ ‘general’ which allow numerous possible concrete realizations they are very ‘economic’ because they use minimal expressions to built many complex meanings. Nevertheless the daily experience with spoken and written expressions shows that they are continuously candidates for false interpretations.

FORMAL MATHEMATICAL WRITTEN EXPRESSIONS

Besides the written expressions of everyday languages one can observe later in the history of written languages the steady development of a specialized version called ‘formal languages’ L_f with many different domains of application. Here I am focusing on the formal written languages which are used in mathematics as well as some pictorial elements to ‘visualize’ the intended ‘meaning’ of these formal mathematical expressions.

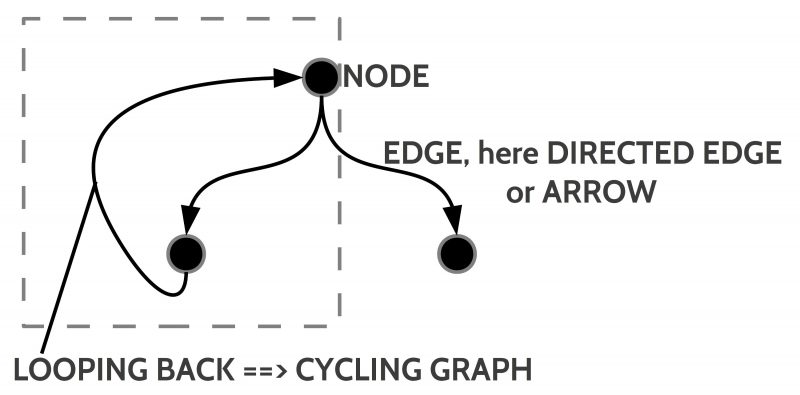

One prominent concept in mathematics is the concept of a ‘graph’. In the basic version there are only some ‘nodes’ (also called vertices) and some ‘edges’ connecting the nodes. Formally one can represent these edges as ‘pairs of nodes’. If N represents the set of nodes then N x N represents the set of all pairs of these nodes.

In a more specialized version the edges are ‘directed’ (like a ‘one way road’) and also can be ‘looped back’ to a node occurring ‘earlier’ in the graph. If such back-looping arrows occur a graph is called a ‘cyclic graph’.

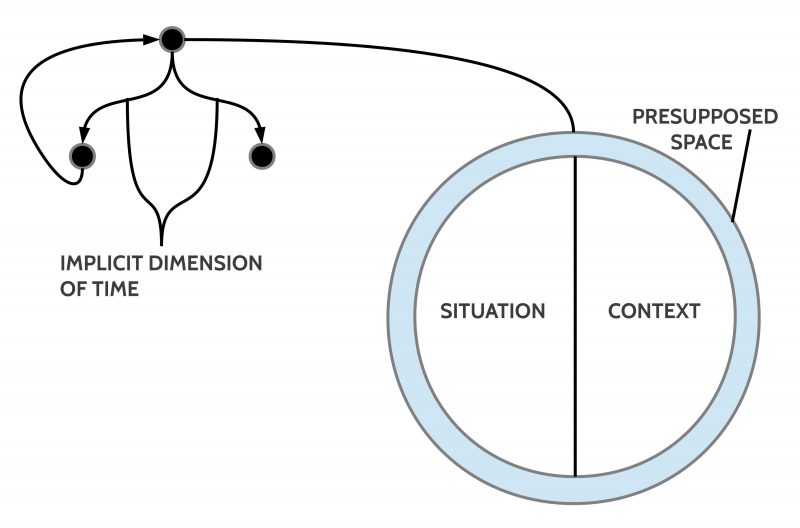

If one wants to use such a graph to describe some ‘states of affairs’ with their possible ‘changes’ one can ‘interpret’ a ‘node’ as a state of affairs and an arrow as a change which turns one state of affairs S in a new one S’ which is minimally different to the old one.

As a state of affairs I understand here a ‘situation’ embedded in some ‘context’ presupposing some common ‘space’. The possible ‘changes’ represented by arrows presuppose some dimension of ‘time’. Thus if a node n’ is following a node n indicated by an arrow then the state of affairs represented by the node n’ is to interpret as following the state of affairs represented in the node n with regard to the presupposed time T ‘later’, or n < n’ with ‘<‘ as a symbol for a timely ordering relation.

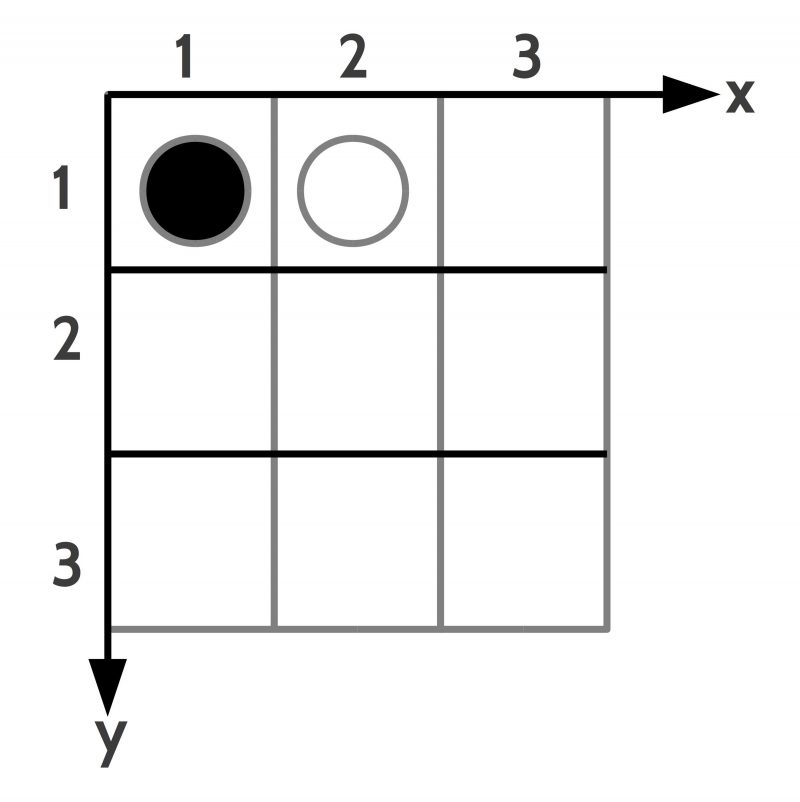

The space can be any kind of a space. If one assumes as an example a 2-dimensional space configured as a grid –as shown in figure 6 — with two tokens at certain positions one can introduce a language to describe the ‘facts’ which constitute the state of affairs. In this example one needs ‘names for objects’, ‘properties of objects’ as well as ‘relations between objects’. A possible finite set of facts for situation 1 could be the following:

- TOKEN(T1), BLACK(T1), POSITION(T1,1,1)

- TOKEN(T2), WHITE(T2), POSITION(T2,2,1)

- NEIGHBOR(T1,T2)

- CELL(C1), POSITION(1,2), FREE(C1)

‘T1’, ‘T2’, as well as ‘C1’ are names of objects, ‘TOKEN’, ‘BACK’ etc. are names of properties, and ‘NEIGHBOR’ is a relation between objects. This results in the equation:

S1 = {TOKEN(T1), BLACK(T1), POSITION(T1,1,1), TOKEN(T2), WHITE(T2), POSITION(T2,2,1), NEIGHBOR(T1,T2), CELL(C1), POSITION(1,2), FREE(C1)}

These facts describe the situation S1. If it is important to describe possible objects ‘external to the situation’ as important factors which can cause some changes then one can describe these objects as a set of facts in a separated ‘context’. In this example this could be two players which can move the black and white tokens and thereby causing a change of the situation. What is the situation and what belongs to a context is somewhat arbitrary. If one describes the agriculture of some region one usually would not count the planets and the atmosphere as part of this region but one knows that e.g. the sun can severely influence the situation in combination with the atmosphere.

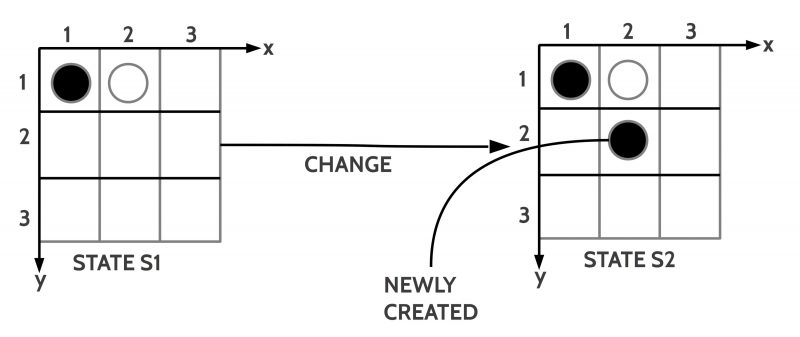

Let us stay with a state of affairs with only a situation without a context. The state of affairs is a ‘state’. In the example shown in figure 6 I assume a ‘change’ caused by the insertion of a new black token at position (2,2). Written in the language of facts L_fact we get:

- TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2), NEIGHBOR(T3,T2)

Thus the new state S2 is generated out of the old state S1 by unifying S1 with the set of new facts: S2 = S1 ∪ {TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2), NEIGHBOR(T3,T2)}. All the other facts of S1 are still ‘valid’. In a more general manner one can introduce a change-expression with the following format:

<S1, S2, add(S1,{TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2), NEIGHBOR(T3,T2)})>

This can be read as follows: The follow-up state S2 is generated out of the state S1 by adding to the state S1 the set of facts { … }.

This layout of a change expression can also be used if some facts have to be modified or removed from a state. If for instance by some reason the white token should be removed from the situation one could write:

<S1, S2, subtract(S1,{TOKEN(T2), WHITE(T2), POSITION(2,1)})>

Another notation for this is S2 = S1 – {TOKEN(T2), WHITE(T2), POSITION(2,1)}.

The resulting state S2 would then look like:

S2 = {TOKEN(T1), BLACK(T1), POSITION(T1,1,1), CELL(C1), POSITION(1,2), FREE(C1)}

And a combination of subtraction of facts and addition of facts would read as follows:

<S1, S2, subtract(S1,{TOKEN(T2), WHITE(T2), POSITION(2,1)}, add(S1,{TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2)})>

This would result in the final state S2:

S2 = {TOKEN(T1), BLACK(T1), POSITION(T1,1,1), CELL(C1), POSITION(1,2), FREE(C1),TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2)}

These simple examples demonstrate another fact: while facts about objects and their properties are independent from each other do relational facts depend from the state of their object facts. The relation of neighborhood e.g. depends from the participating neighbors. If — as in the example above — the object token T2 disappears then the relation ‘NEIGHBOR(T1,T2)’ no longer holds. This points to a hierarchy of dependencies with the ‘basic facts’ at the ‘root’ of a situation and all the other facts ‘above’ basic facts or ‘higher’ depending from the basic facts. Thus ‘higher order’ facts should be added only for the actual state and have to be ‘re-computed’ for every follow-up state anew.

If one would specify a context for state S1 saying that there are two players and one allows for each player actions like ‘move’, ‘insert’ or ‘delete’ then one could make the change from state S1 to state S2 more precise. Assuming the following facts for the context:

- PLAYER(PB1), PLAYER(PW1), HAS-THE-TURN(PB1)

In that case one could enhance the change statement in the following way:

<S1, S2, PB1,insert(TOKEN(T3,2,2)),add(S1,{TOKEN(T3), BLACK(T3), POSITION(2,2)})>

This would read as follows: given state S1 the player PB1 inserts a black token at position (2,2); this yields a new state S2.

With or without a specified context but with regard to a set of possible change statements it can be — which is the usual case — that there is more than one option what can be changed. Some of the main types of changes are the following ones:

- RANDOM

- NOT RANDOM, which can be specified as follows:

- With PROBABILITIES (classical, quantum probability, …)

- DETERMINISTIC

Furthermore, if the causing object is an actor which can adapt structurally or even learn locally then this actor can appear in some time period like a deterministic system, in different collected time periods as an ‘oscillating system’ with different behavior, or even as a random system with changing probabilities. This make the forecast of systems with adaptive and/ or learning systems rather difficult.

Another aspect results from the fact that there can be states either with one actor which can cause more than one action in parallel or a state with multiple actors which can act simultaneously. In both cases the resulting total change has eventually to be ‘filtered’ through some additional rules telling what is ‘possible’ in a state and what not. Thus if in the example of figure 6 both player want to insert a token at position (2,2) simultaneously then either the rules of the game would forbid such a simultaneous action or — like in a computer game — simultaneous actions are allowed but the ‘geometry of a 2-dimensional space’ would not allow that two different tokens are at the same position.

Another aspect of change is the dimension of time. If the time dimension is not explicitly specified then a change from some state S_i to a state S_j does only mark the follow up state S_j as later. There is no specific ‘metric’ of time. If instead a certain ‘clock’ is specified then all changes have to be aligned with this ‘overall clock’. Then one can specify at what ‘point of time t’ the change will begin and at what point of time t*’ the change will be ended. If there is more than one change specified then these different changes can have different timings.

THIRD PERSON VIEW

Up until now the point of view describing a state and the possible changes of states is done in the so-called 3rd-person view: what can a person perceive if it is part of a situation and is looking into the situation. It is explicitly assumed that such a person can perceive only the ‘surface’ of objects, including all kinds of actors. Thus if a driver of a car stears his car in a certain direction than the ‘observing person’ can see what happens, but can not ‘look into’ the driver ‘why’ he is steering in this way or ‘what he is planning next’.

A 3rd-person view is assumed to be the ‘normal mode of observation’ and it is the normal mode of empirical science.

Nevertheless there are situations where one wants to ‘understand’ a bit more ‘what is going on in a system’. Thus a biologist can be interested to understand what mechanisms ‘inside a plant’ are responsible for the growth of a plant or for some kinds of plant-disfunctions. There are similar cases for to understand the behavior of animals and men. For instance it is an interesting question what kinds of ‘processes’ are in an animal available to ‘navigate’ in the environment across distances. Even if the biologist can look ‘into the body’, even ‘into the brain’, the cells as such do not tell a sufficient story. One has to understand the ‘functions’ which are enabled by the billions of cells, these functions are complex relations associated with certain ‘structures’ and certain ‘signals’. For this it is necessary to construct an explicit formal (mathematical) model/ theory representing all the necessary signals and relations which can be used to ‘explain’ the obsrvable behavior and which ‘explains’ the behavior of the billions of cells enabling such a behavior.

In a simpler, ‘relaxed’ kind of modeling one would not take into account the properties and behavior of the ‘real cells’ but one would limit the scope to build a formal model which suffices to explain the oservable behavior.

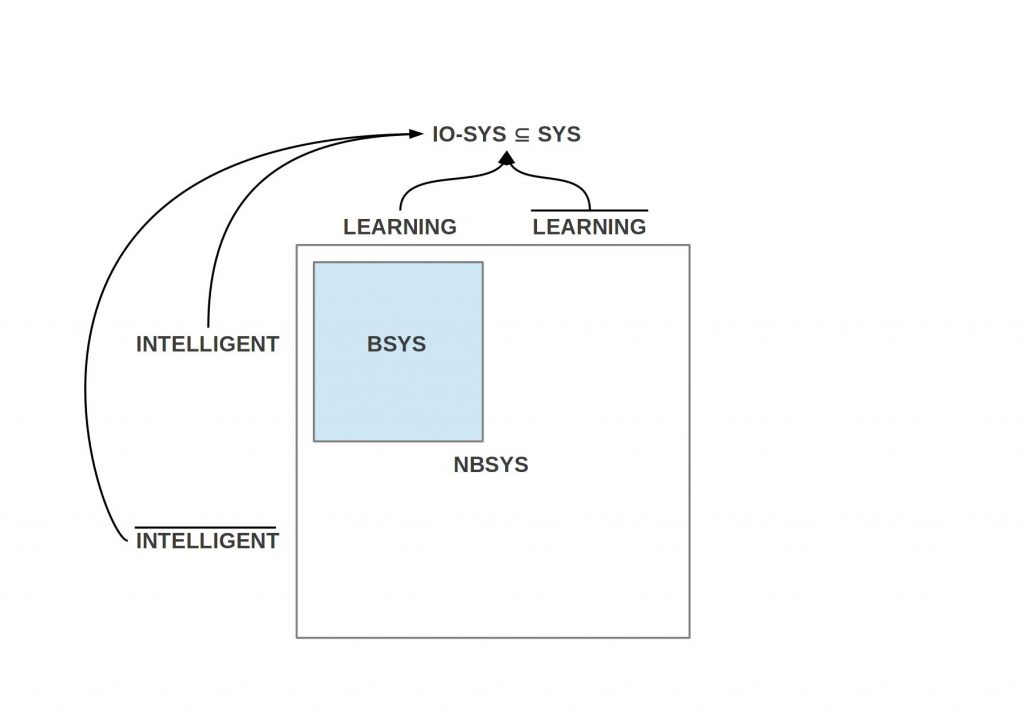

This kind of approach to set up models of possible ‘internal’ (as such hidden) processes of an actor can extend the 3rd-person view substantially. These models are called in this text ‘actor models (AM)’.

HIDDEN WORLD PROCESSES

In this text all reported 3rd-person observations are called ‘actor story’, independent whether they are done in a pictorial or a textual mode.

As has been pointed out such actor stories are somewhat ‘limited’ in what they can describe.

It is possible to extend such an actor story (AS) by several actor models (AM).

An actor story defines the situations in which an actor can occur. This includes all kinds of stimuli which can trigger the possible senses of the actor as well as all kinds of actions an actor can apply to a situation.

The actor model of such an actor has to enable the actor to handle all these assumed stimuli as well as all these actions in the expected way.

While the actor story can be checked whether it is describing a process in an empirical ‘sound’ way, the actor models are either ‘purely theoretical’ but ‘behavioral sound’ or they are also empirically sound with regard to the body of a biological or a technological system.

A serious challenge is the occurrence of adaptiv or/ and locally learning systems. While the actor story is a finite description of possible states and changes, adaptiv or/ and locally learning systeme can change their behavior while ‘living’ in the actor story. These changes in the behavior can not completely be ‘foreseen’!

COGNITIVE EXPERT PROCESSES

According to the preceding considerations a homo sapiens as a biological system has besides many properties at least a consciousness and the ability to talk and by this to communicate with symbolic languages.

Looking to basic modes of an actor story (AS) one can infer some basic concepts inherently present in the communication.

Without having an explicit model of the internal processes in a homo sapiens system one can infer some basic properties from the communicative acts:

- Speaker and hearer presuppose a space within which objects with properties can occur.

- Changes can happen which presuppose some timely ordering.

- There is a disctinction between concrete things and abstract concepts which correspond to many concrete things.

- There is an implicit hierarchy of concepts starting with concrete objects at the ‘root level’ given as occurence in a concrete situation. Other concepts of ‘higher levels’ refer to concepts of lower levels.

- There are different kinds of relations between objects on different conceptual levels.

- The usage of language expressions presupposes structures which can be associated with the expressions as their ‘meanings’. The mapping between expressions and their meaning has to be learned by each actor separately, but in cooperation with all the other actors, with which the actor wants to share his meanings.

- It is assume that all the processes which enable the generation of concepts, concept hierarchies, relations, meaning relations etc. are unconscious! In the consciousness one can use parts of the unconscious structures and processes under strictly limited conditions.

- To ‘learn’ dedicated matters and to be ‘critical’ about the quality of what one is learnig requires some disciplin, some learning methods, and a ‘learning-friendly’ environment. There is no guaranteed method of success.

- There are lots of unconscious processes which can influence understanding, learning, planning, decisions etc. and which until today are not yet sufficiently cleared up.